Did Teamdouble Dragon Stop Ck2 Again

Giant Flop News

110 Comments

Off The Clock: My Own Personal Investigation Team

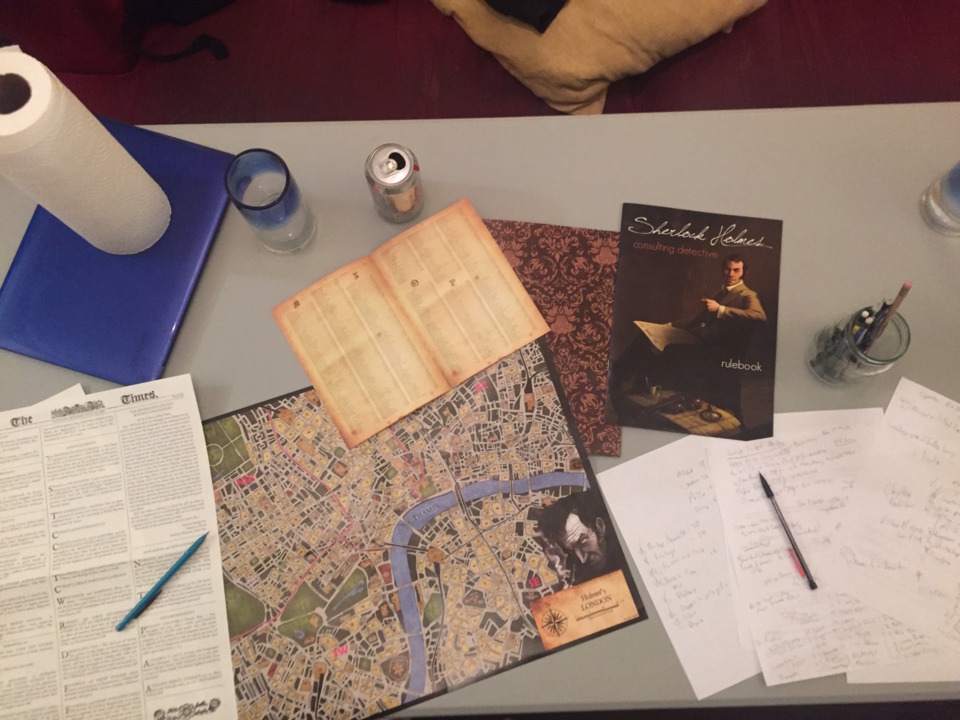

After years of trying to make it happen, I finally got to play Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective. I was not disappointed.

Welcome to Off the Clock, my weekly column about the stuff I've been doing while out of the role. This weekend, I spent my complimentary fourth dimension…

Solving Mysteries

Afterwards years of trying to detect an affordable copy of Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective (plus a handful of friends willing and able to play with me), I finally got the opportunity to dig into this classic mystery/adventure game. (There'southward an FMV adaptation of the board game, likewise, but I don't really accept whatsoever experience with that.)

For the uninitiated, Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective casts the players as the Bakery Street Irregulars, a group of misfit investigators that Holmes occasionally relies on for information gathering and reconnaissance. At the start of the game one thespian reads aloud from a case booklet, setting upwardly a murder or a theft or some other mystery that needs to be figured out. Once the introduction is over, players race confronting Holmes to try and solve it.

How practise you practise that? Well, you exercise what any good investigators would practise. You curl out a map of London, peruse the day's newspaper, and flip through a hefty "directory"--sort of like a telephone book--and decide where in town to go. Every building in town has a designator (Buckingham Palace is SW35, for instance), and when you determine where you desire to go you, you open up the case booklet to that designator and read the text that's written there. It could be a long, multi-page interview with a suspect or a short paragraph almost something (seemingly) irrelevant to your investigation. Sometimes it's nothing at all… whoops. Once you think you have a handle on what happened, you plow to the end of the instance booklet and endeavor to answer six questions posed by Holmes about the crime (and its adjacent intrigues). You get points for getting the answer right and lose points for taking more than turns (that is, visiting more points on the map) than Holmes did.

None of this would piece of work if the mysteries were simple riddles (or even complex logic puzzles). If all you lot had to do was assemble the show and line it up nicely, SH:CD wouldn't produce that special sensation that you go when you finally do figure something out. You can't have the feeling of finding a needle in a haystack without the hay, and you tin can't feel like yous've unraveled someone's carefully guarded secret life without their life feeling messy and filled with irrelevant details.

It's really hard to overstate the latitude of data available for you to find in whatever individual example. In our starting time game, the CEO of an arms manufacturing company was plant expressionless in an alley exterior company headquarters, and even after visiting multiple locations and getting what we thought was a fair amount of information on the instance, we still had a lot of questions. Was the killing due to internal strife at the company? Was it tied to international corporate or military intrigue? Was a scorned lover involved, and if so which one? Each of these questions emerged out of multiple investigation points, seated carefully in a diverseness of sub-stories and graphic symbol perspectives.

The first time through, nosotros played with the intention of "winning" the game--largely because the Holmes of SH:CD is merely equally smug as his literary original. So, after just 10 turns, we convinced ourselves that nosotros knew what happened and we went dorsum to 221B Baker Street. Nosotros flipped to the back of the book, answered Holmes' questions, read his solutions and realized that we could not have been more wrong. Whoops, once again.

It was a learning experience, not but because nosotros understood the game improve, merely considering nosotros learned what we wanted from the game. So we started the 2d case (this time well-nigh the death of an octogenarian full general, the Battle of Waterloo, and… a jewel heist? Maybe?), and we decided to take a much less competitive attitude. In a sense, we were playing information technology the way many played Her Story, the database driven mystery game that got a ton of attending before this twelvemonth. We weren't racing against Sherlock, we committed to investigating until we were satisfied. (And, for the tape, we all the same got things incorrect. Don't rent us as your detectives, I guess.)

Honestly, it's hard non to compare SH:CD to Her Story. Both are games that feature open-concluded investigation, and SH:CD is a smashing reminder that Her Story shouldn't be lauded just for being "fresh," either. Every bit Twitter user @VorpalFemme pointed just later on information technology released, Her Story is not the commencement game on the marketplace to feature database diving and non-linear storytelling. She notes that Christine Love's Digital: A Love Story and Counterpart: A Hate Story both allow players dig through e-mail correspondence in a way similar to Her Story'southward faux-desktop detective work. Taken more broadly, Emily Short'southward Galatea and First Typhoon of the Revolution offer unique takes on interactive exposition that blur the line between narrative "exploration" and authorship. And on a recent episode of Idle Thumbs, Nick Breckon realizes that Ancestry.com's uses "multiplayer" hooks and game-y advantage systems to encourage a like sort of "ane-more than-click" style of play.

It's easy to find ourselves saying something similar "Game X has washed something no other game has washed before," but nosotros should exist careful of making those sorts of claims. The structure of the manufacture has historically made it easier for some games to "pierce" into the wider consciousness than others, and (though it'due south a abiding challenge) nosotros should practice our best to broaden the scope of our knowledge about the medium instead of making hyperbolic claims about originality. Beyond that, though, we should also do more than only say "this game is good because information technology does something new," since humid any of these games downwards to their novelty alone does them a disservice. Instead, we should engage with their specific qualities. How do they execute on the concept of not-linear storytelling? What particular feeling does investigation create for the thespian in these games?

In the case of Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective, information technology is the game'south quality of materiality that distinguishes it for me. It'due south the feeling of flipping through pages, pointing at spot on the shared map on a table, measuring the altitude traveled by a suspect to see if their alibi adds upwardly. Information technology'southward fifty-fifty the fact that "the answers" exist in the book, waiting to exist seen, constantly tempting your optics. When I say "materiality," I mean more than only the game's physical attributes, besides: Even the manner the game is designed feels, somehow, touchable and existent. For case, as you consummate cases, previous newspapers remain "in play"--in the 2d instance we establish an of import clue in the broadsheet from in-game months prior. Your knowledge most the city and its inhabitants increases as you play, too, and information technology's easy to detect yourself slipping into character: "Well… Nosotros practice know that guy at the city records section… Perchance he could tell us something?"

It's a more objective-oriented mystery than Her Story and a less emotional one than Counterpart, merely it took me over in a way that neither of those games did. To elevator a term from virtual reality marketing, information technology's a game with presence. Simply as, in the Elite: Unsafe VR demo, I forgot for the slightest moment that the pilot's paw wasn't actually my hand, there were moments playing Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective where my encephalon's neurons fired in a confused pattern, then certain that I was cracking a real, important mystery broad open up. Brief moments, yes, but intense all the aforementioned. A quarter 2d hither, where I realize that someone'due south alibi doesn't add upward; a half 2d there, when the evidence I've been hoping to detect for the last two hours first springs into view; the length of the grin I gave my friend as he read the damning witness testimony aloud.

So far, I've worked through two of the game's ten cases. That means there are viii more mysteries to solve... plus an expansion due sometime in 2016. I cannot look to swoop back into the streets of London again.

A quick question for you all, though: So much of my experience of Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective inverse when we decided to focus on solving the mystery instead of simply trying to beat Sherlock'southward score. Do you have any gaming experiences where, because you shifted your focus/goals, your experience was greatly improved? Maybe you lowered (or increased) the difficulty in an FPS or maybe you lot decided to play as a different class in an RPG? Maybe it'south even nigh who (or where, or when) you decided to play something? Permit me know!

Oh, and because our answers have been so good every week, I'm going to outset grabbing a handful of my favorite comments and highlighting them in a postal service every Fri afternoon! If you'd adopt your answer not to be included in that post, let me know and I'll respect that.

I as well spent some this fourth dimension this week...

Listening to: "Sunshine" by Pusha T

Reading: "Get rich or die vlogging: The sad economics of cyberspace fame" by Gaby Dunn

Watching: Rifftrax's Star Wars Holiday Special Commentary (Go for the Wookies, stay for the 70s TV ads).

Source: https://www.giantbomb.com/articles/off-the-clock-my-own-personal-investigation-team/1100-5326/?comment_sort=m.dateCreated&comment_direction=ASC&comment_page=2

0 Response to "Did Teamdouble Dragon Stop Ck2 Again"

Post a Comment